Introduction 2025

Full scores of the following pieces are available on request in PDF format:

The Probability of Harmony (A3 landscape)

Possible Developments (327x285mm for A3 landscape)

Vectors (380x495mm for A2 portrait)

beyond the symbolic (390x297mm for A3 landscape)

The Innocent Bystander (A4 portrait)

Performance material for these pieces is also available as follows:

The Probability of Harmony (PDFs, WAVs)

Possible Developments (paper)

Vectors (paper)

beyond the symbolic (paper)

The Innocent Bystander (paper — the choir sings from the score.)

Contact information can be found

here.

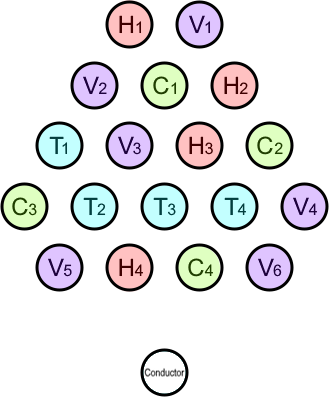

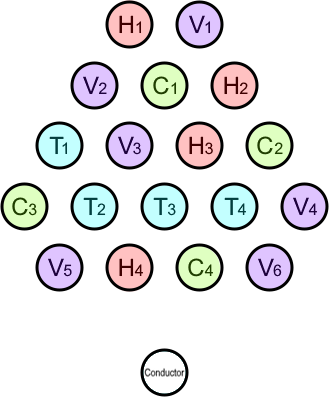

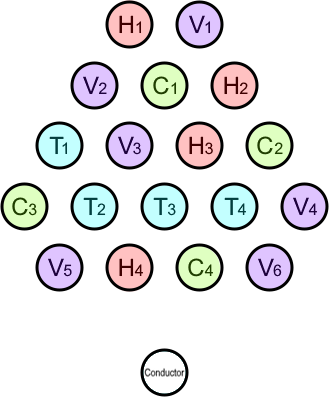

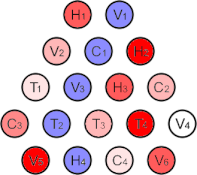

Vectors is for:

seated as follows, slightly further apart than usual, on a stage that is as steeply raked as possible with respect to the audience:

(The colours are simply helping to identify the instrument types.)

The piece was composed 1974-76 and performed at the Donaueschinger Musiktage 1978.

While at college,

studying with Harrison Birtwistle (1968-71), I was unhappy with the way the notational experiments of the ’50s and ’60s had simply been brushed aside (1970) without any explanation, and had therefore decided to re-think music notation from scratch. I wanted to use music symbols only when I thought I really understood them, and to use experimental compositions as a way to develop that understanding.

Two small pieces,

The Probability of Harmony and

Possible Developments precede

Vectors. These use standard five-line staves, clefs and standard pitch symbols, but the durations are only relative. Durations are decided spontaneously, following rehearsals in which a performance practice has been developed.

Defining duration classes using precise metronome marks conflicts with actual musical practice,

but I wanted to use them in order to enrich the logical possibilities of the notation. So

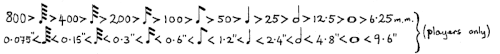

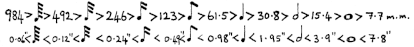

Vectors examines the consequences of defining them as

ranges of duration. The piece was also a vehicle for thinking about the relations between

performance space and musical material (see

the original program note below). This was obviously a major topic in

New Music at the time. Stockhausen was not the only one working in this area: Birtwistle (e.g.

Verses for Ensembles) was also on my mind.

I learned, during the composition of Vectors, how important it is to distinguish between space and time in scores. Duration class symbols are objects in space, so the following composition, beyond the symbolic, defines them as ranges of space, leaving their durations free to be defined using human memory and performance practice.

Vectors was composed using krystal expansions defined using vectors in expansion fields (see

A short introduction to krystals). The piece has 7 heterogenous sections, each of which examines the consequences of defining duration classes as ranges of

time. It begins with a chaotic explosion, and ends with independent threads dissipating into nothingness.

beyond the symbolic follows this ending by investigating the control of such lines using rules of counterpoint.

Vectors is dedicated to my family and friends, and can also be read biographically, in relation to the upheavals going on in my life at the time: My father died on 4th August 1974 while I was in Germany working on Inori... The search for meaning had become more important than ever.

Acknowledgements:

Vectors was composed 1974-76 in Swanley (England) at my parent’s house, Kürten (West Germany), and in Eynsford (England) at the house to which my mother had moved.

Special thanks go to Karlheinz Stockhausen for the gift of two months of peace at his home in January/February 1976, during which the bulk of section

was conceived and executed.

It was also largely thanks to Stockhausen that the piece was performed at the Donaueschinger Musiktage 1978.

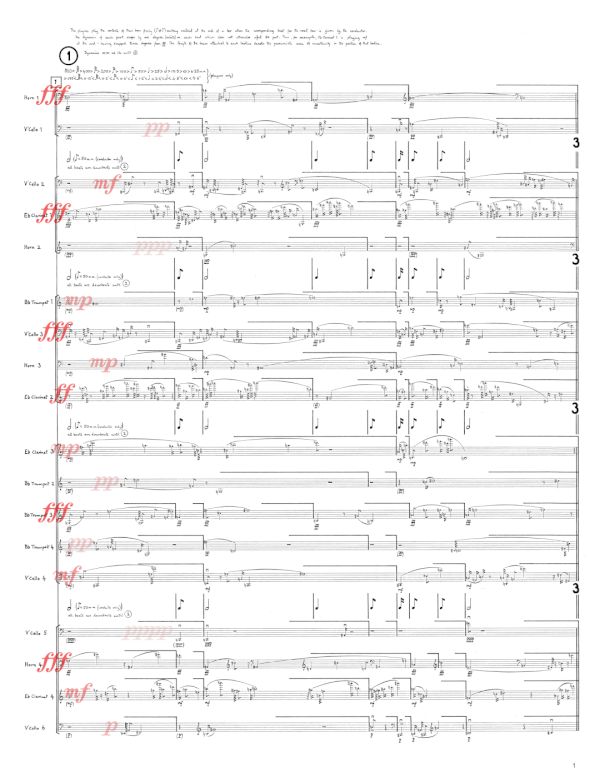

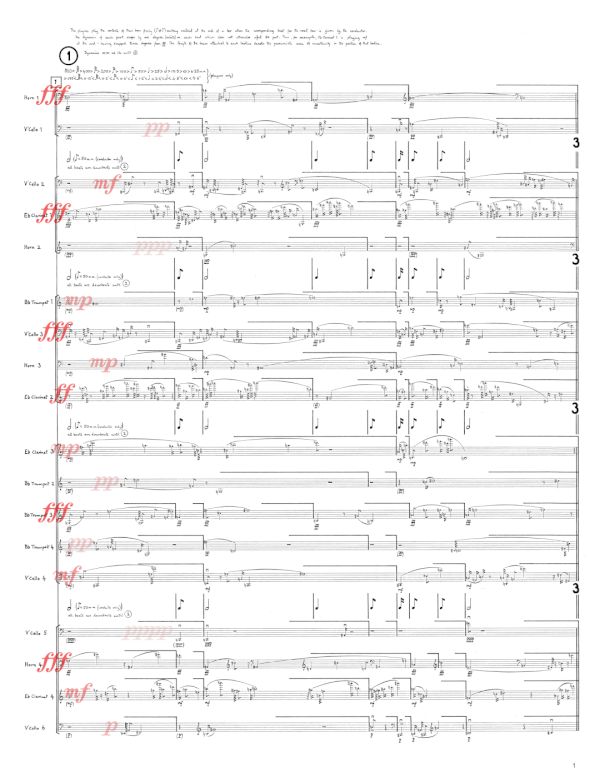

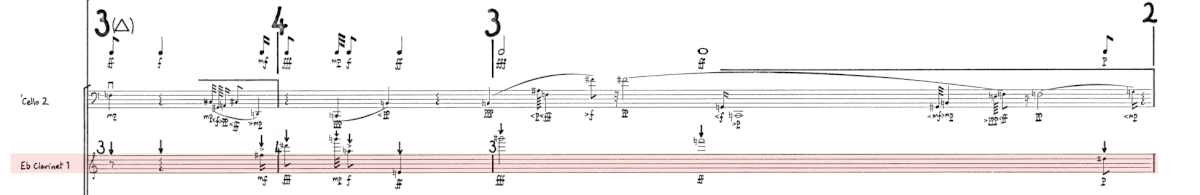

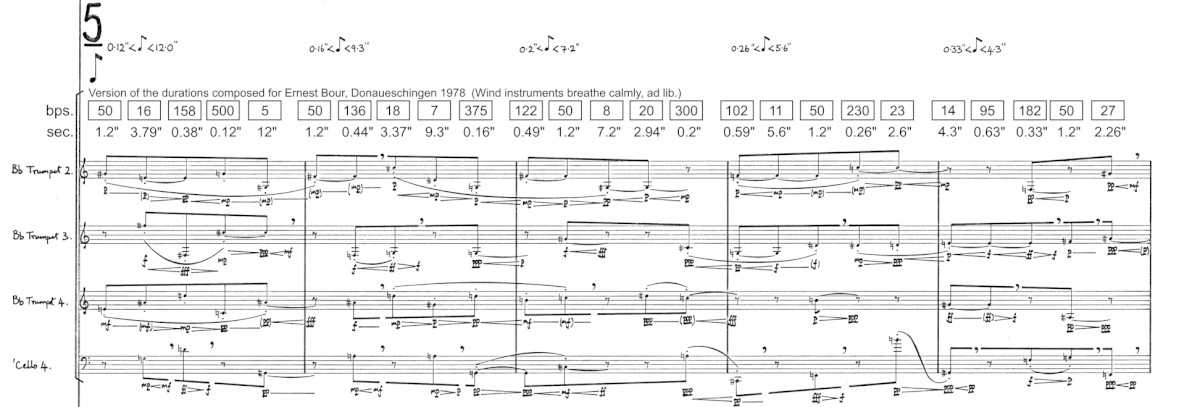

Examples from the score

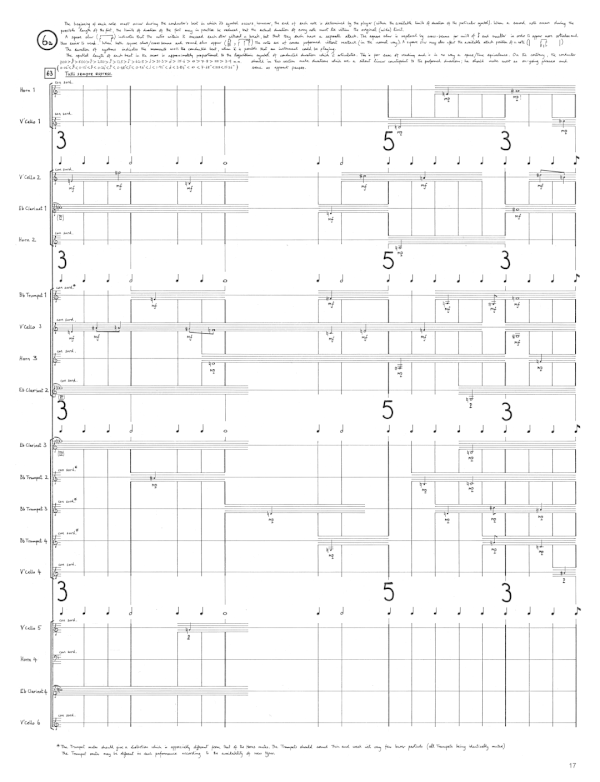

Section  (page 1 of 37)

(page 1 of 37)

A “chaotic explosion’ is realized using stratified dynamics that create depth. Each player begins at his/her base dynamic with each new “bar”, reducing it at the conducters other beats.

The performance instructions (at the top of the page) read as follows:

Page 1 overview:

Red dynamics have been added here to clarify the players' dynamics. They are not in the original score.

Page 1 detail:

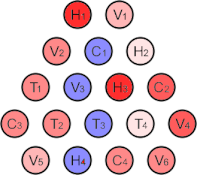

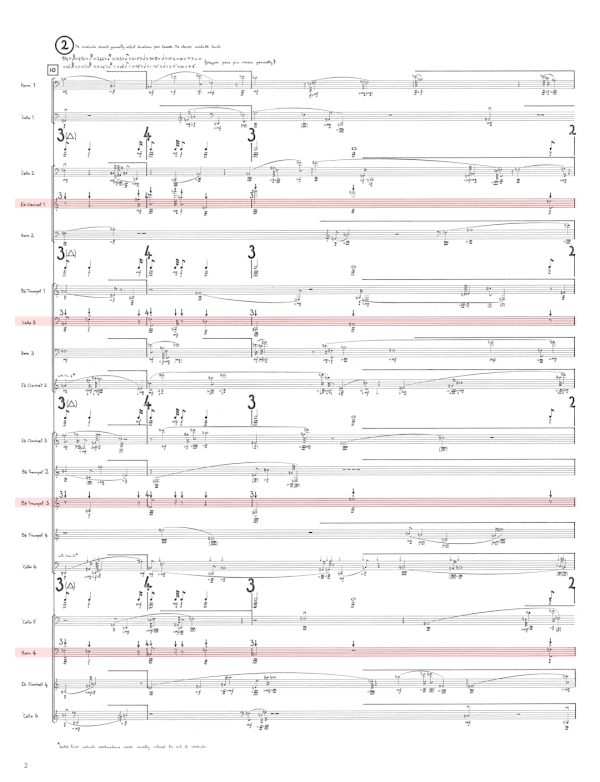

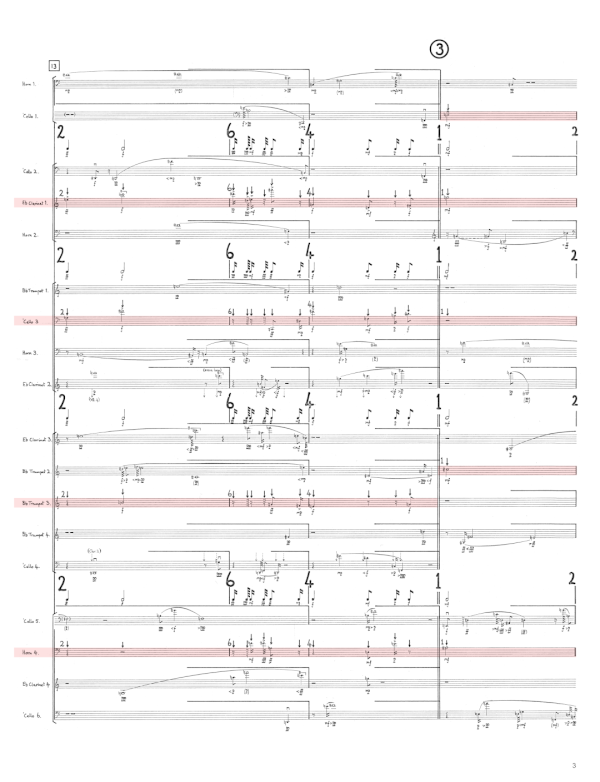

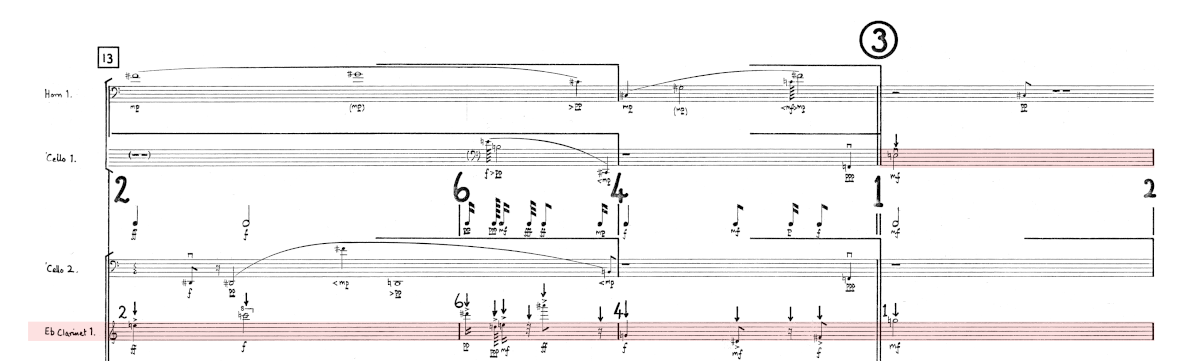

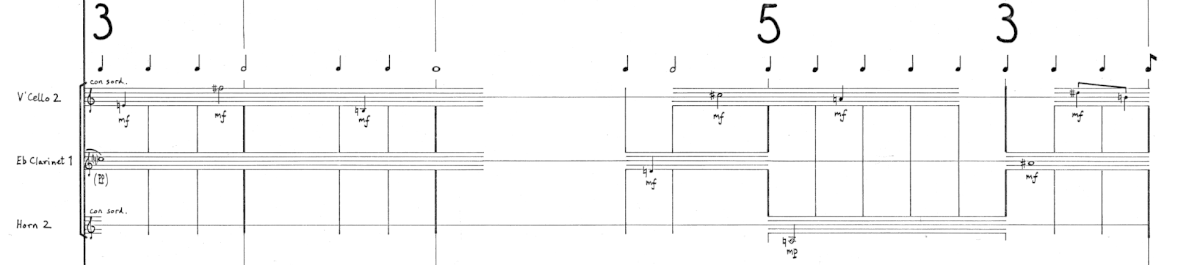

Sections  and

and  (pages 2-3 and 3-13 of 37)

(pages 2-3 and 3-13 of 37)

Individual notes now have their own dynamic.

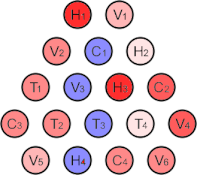

The instruments are divided into 6 Groups, each of which has a generally different dynamic level and density of music to play.

In

, Group 1 (coloured blue below) plays synchronous, conducted chords.

The Groups are, in order of general loudness (loud to quiet):

Group 1: Clarinet 1, V’Cello 3, Trumpet 3, Horn 4

Group 2: Horn 1, Horn 3

Group 3: Clarinet 2, V’Cello 4

Group 4: V’Cello 2, Trumpet 1, Clarinet 3, Trumpet 2, Clarinet 4, V’Cello 6

Group 5: V’Cello 1, V’Cello 5

Group 6: Horn 2, Trumpet 4

Group 1 (synchronous chords) is coloured blue here.

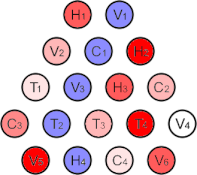

In

Group 2 (coloured blue below) always plays synchronous, conducted chords.

The Groups are, in order of initial general loudness (loud to quiet):

Group 1: Horn 2, Trumpet 4, V’Cello 5

Group 2: V’Cello 1, Clarinet 1, V’Cello 3, Trumpet 2, Horn 4

Group 3: Horn 1, Horn 3, V’Cello 6

Group 4: Clarinet 3

Group 5: V’Cello 2, Clarinet 2, Trumpet 3

Group 6: Trumpet 1, Clarinet 4

(V’Cello 4 is tacet.)

Group 2 (synchronous chords) is coloured blue here.

During the course of

, the seating positions are used to control gradual changes in the players’ material.

[Self-critique 2025: In retrospect, it would have been better if these changes had been clearer and more drastic. Krystals were an experimental technology, and I was trying to solve too many problems at once — a beginner, still finding his feet...]

The performance instructions (at the top of page 2) read as follows:

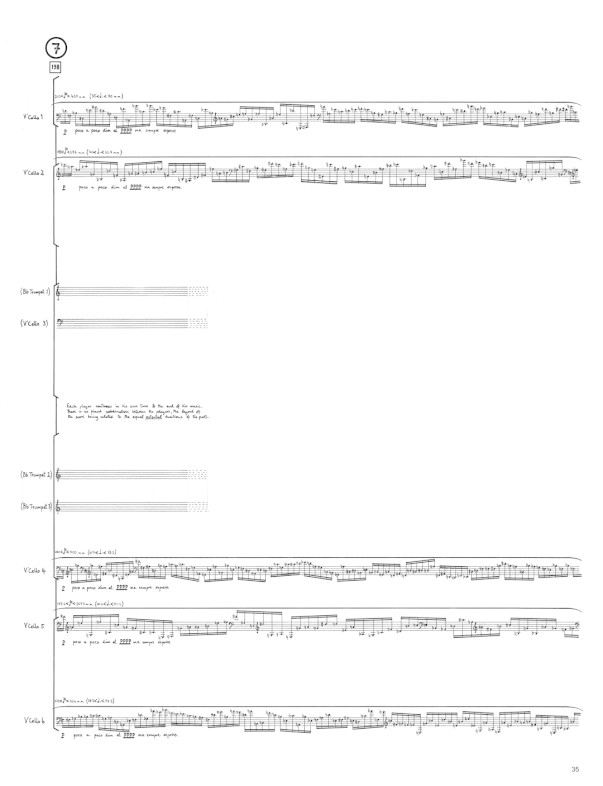

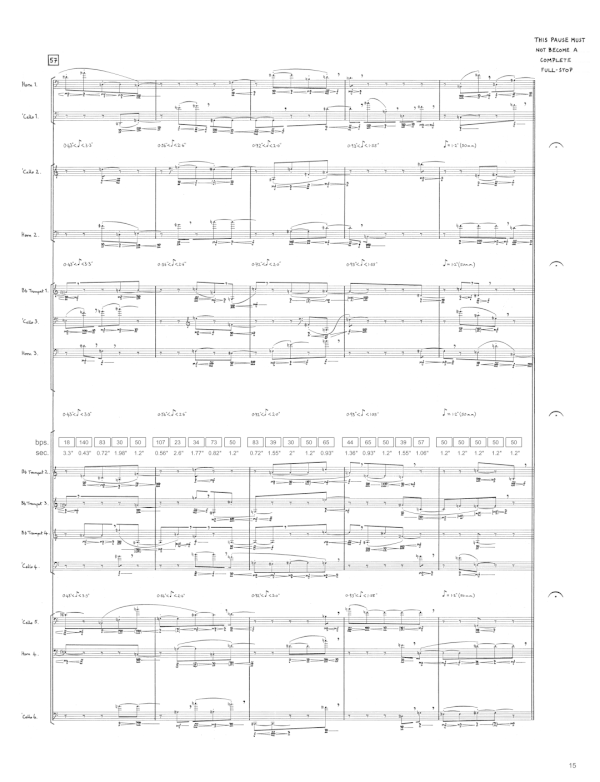

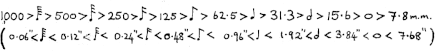

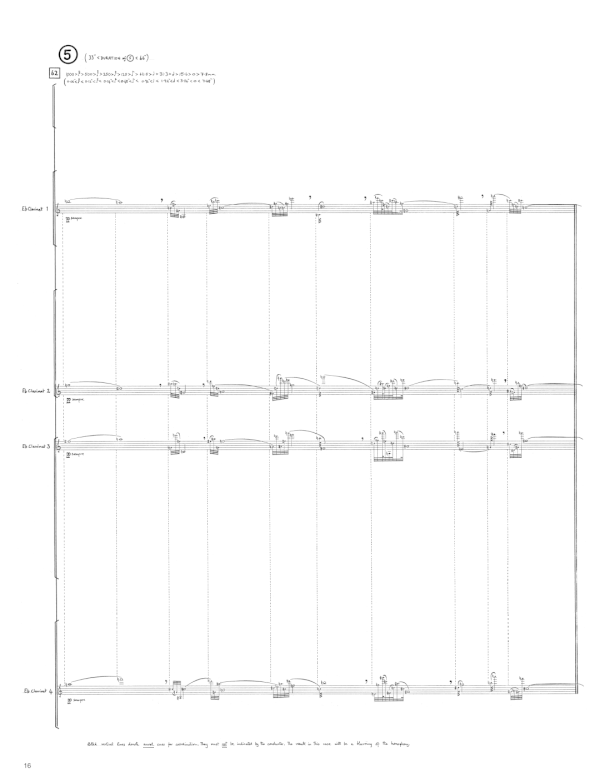

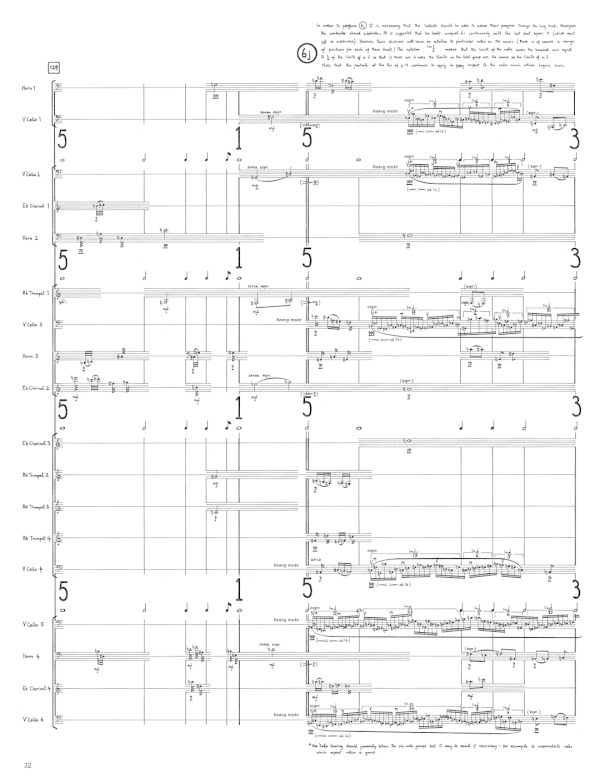

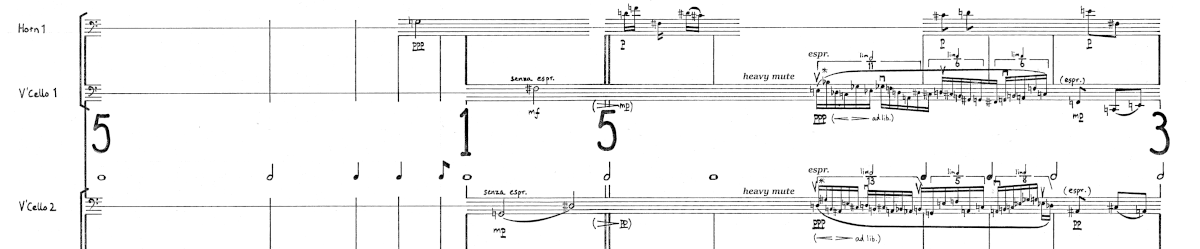

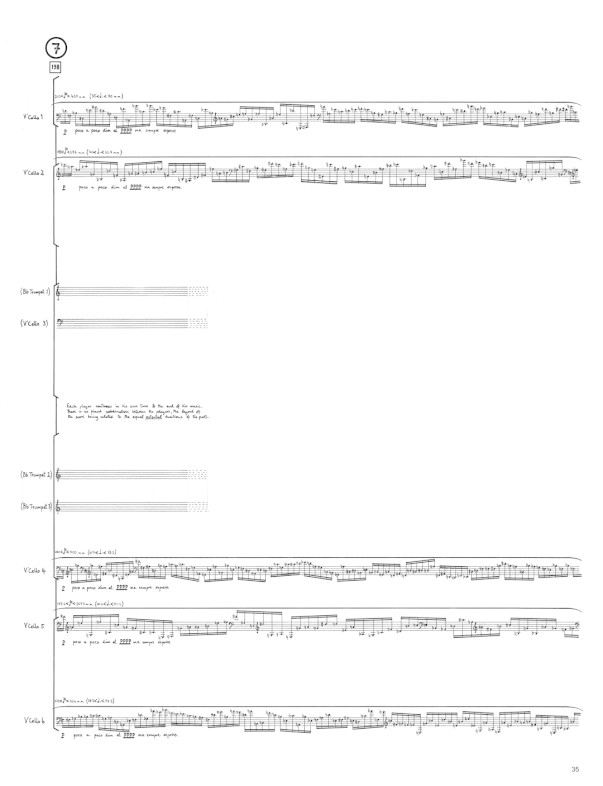

Section

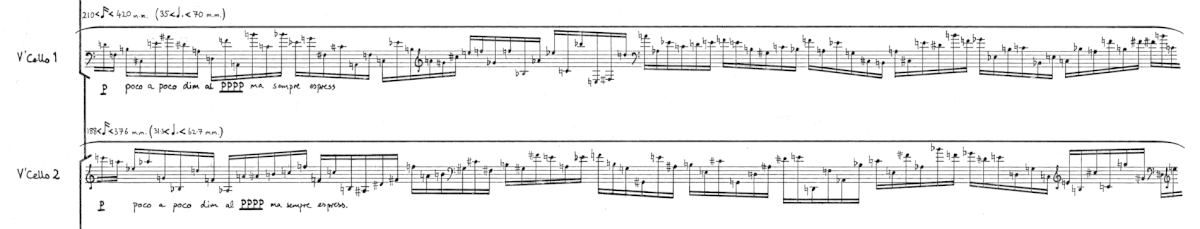

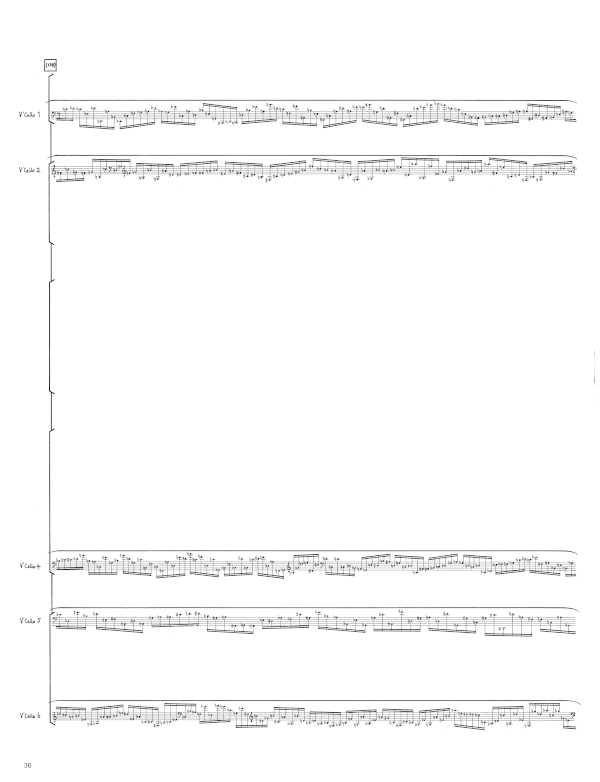

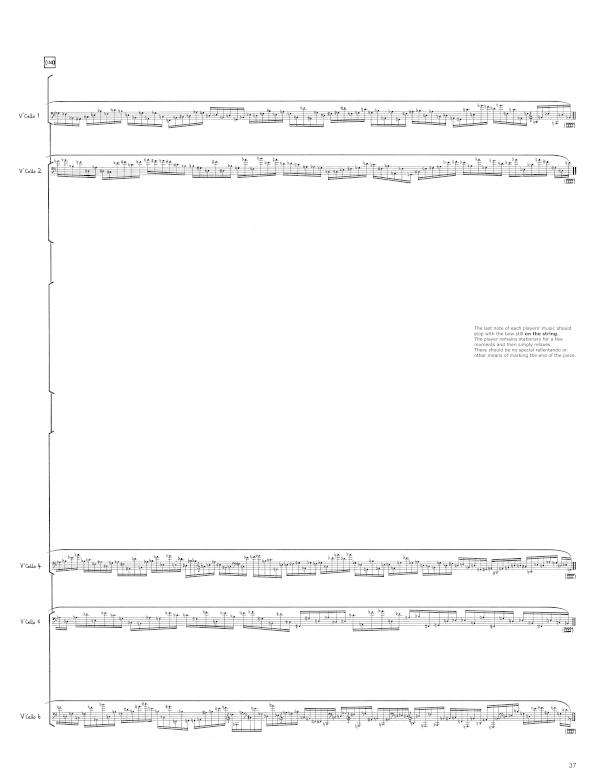

(pages 35-37 of 37)

(pages 35-37 of 37)

The piece ends with uncoordinated lines, like the dying remains of an exploded firework.

The following composition, beyond the symbolic, is about counterpoint.

The music for section

actually begins at

on page 32 (see above).

The performance instructions on this page (35) are as follows:

Page 35 overview

Page 35 detail

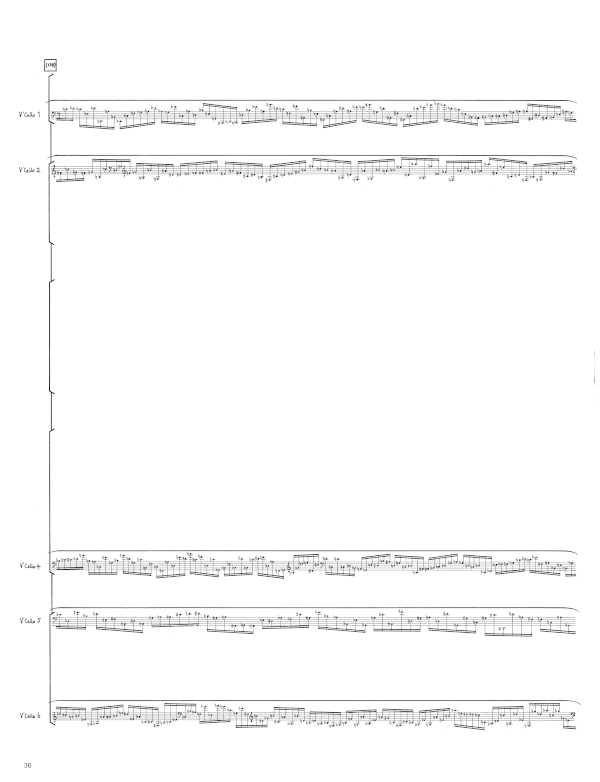

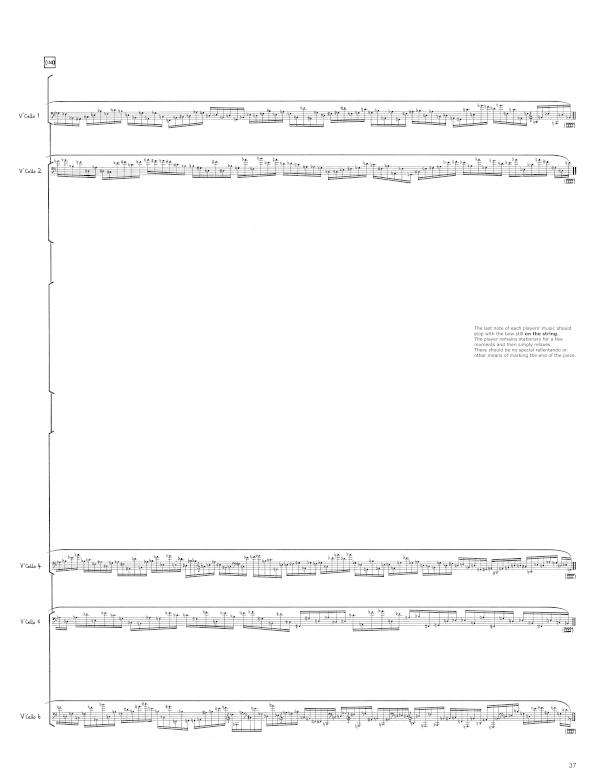

Pages 36 and 37 overview

The performance instructions at the end of the final page (37) are as follows:

The last note of each players’s music should stop with the bow still on the string.

The player remains stationary for a few moments and then simply relaxes. There should be no special rallentando or other means of specially marking the end of the piece.

The original performance instructions (1978)

These are the performance instructions in the score.

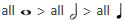

In this piece, no durations may be subdivided either mentally by the players or physically by the conductor unless there is an indication to the contrary. Thus, while durations may be of the same order

, none is comensurable. It follows from this that it is impossible to be sure of accuracy at the given limits of the durations. However, within each “tempo” field every player should ensure that

etc. This is exactly equivalent to the situation in metred music where it is impossible to guarantee the metronomic value of a beat, but it is possible to ensure that all beats are “equal”. Each duration in

Vectors must be felt as a continuous phenomenon whose end-points are dictated by the phrasing alone, and not as the distance between two preconceivable points. For example, section

ends with a bar marked

but the beats remain of the same form as those in the rest of the piece. This is not a bar in which the beats are equated with a regular pulse, it is rather the limit of an approximation.

The horizontal beam stretching backwards from each barline in sections

covers the available positions of that barline with respect to the music notated beneath it. Each player performs his or her music freely within the given limits of duration, jumping to the next bar when it is given by the conductor, omitting any material which lies between. This jump should always occur from a point under a horizontal beam. However, the notes which occur immediately after the barlines in these sections need not be completely simultaneous unless accompanied by a vertical arrow. They are nevertheless nearly so,

In section

, the conductor should mentally subdivide the beats. (This is the closest relation to metred music in the piece.) The horizontal beams are passive in this section, merely confirming the duration limits given — the performers being totally free within these limits. The conductor may, if he or she wishes, group the beats in twos or fours.

In sections

and

however, the horizontal beams are active. In order that jumps are always made from beneath a beam it is necessary that the conductor should choose durations which lie towards the long ends of the available limits and the players should choose generally faster durations. However, the total range of durations is available to both conductor and performers.

Sections

are a development towards an equivalent of the subdivisions in metred music (whereby a

may be replaced by

for example) by the controlled loosening of a homophony. The instruction at

applies equally to the ’Cello music at

and in section

. For example, it is not necessary for ’Celli 5 and 6 to start simultaneously at

— they may start a little later, non-simultaneously. But each note that occurs within a given conducted beat should begin within that beat. The ’Celli in

and

should continue to make full use of the available flexibility.

The original program note (Donaueschingen 1978)

Vectors was given its first and, in 2025, only performance, as part of the Donaueschinger Musiktage, on Sunday 22nd Oktober 1978, by the Südwestfunk Orchestra conducted by Ernest Bour.

This program note was printed, in a German translation by Josef Häusler,

in the festival program.

Form

Vectors was conceived as a catalyst and as a vehicle for the development of my theoretical work. Its overall form was not predetermined but is the result of successive decisions made in the light of experienced gained in the previous sections. I wanted, by this means, to create a real progression from one section to the next and to achieve a tangible structural discrepancy between the first section and the last. Unity has, I believe, become too inevitable to be emphasized as a formal principle.

It is characteristic of such a structure that there is no real end-point (in fact a further section was partially planned), but I discovered in connection with this particular piece that the decision to stop became exactly as logical, or illogical, as the original decision to start and therefore had no difficulty in coming to a halt. However, with hindsight and much ambiguity, each section can be said to function in an overalll form. For example, it is possible, but not inevitable, that the last section can be heard as the open-form equivalent of a cadence.

Content

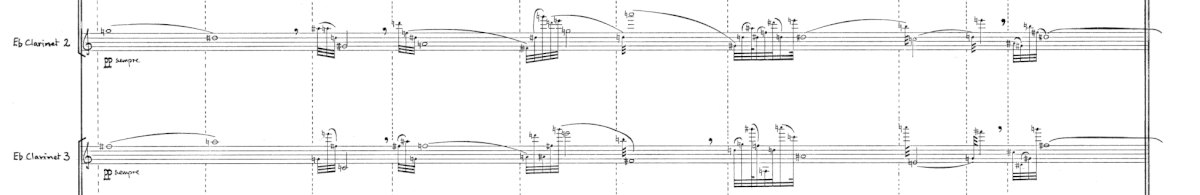

There are many separate but related lines of thought within the substructures of

Vectors. The most obvious to a reader of the score is a concern to discover some of the consequences arising from a redefinition of the duration symbols (

,

,

etc.). I have used them here to describe bands of possible durations, one octave

1 each in width. It follows from this condition that exact performed durations are not predictable, and that they are

not subdividable. Further results of this situation are that the ability to create multiple simultaneity of attack is concentrated in the hands of the conductor, and that there is a strong separation of the functional characteristics of attack, duration and release. It is perhaps interesting to remember that the traditional symbols for dynamic, the other dimension of size, also express bands of possible values.

The eighteen players are distributed on a 60° grid and are somewhat more separated from each other than is usually the case, so that the ensemble becomes neither a clear unit nor a group of isolated individuals. I have treated the space strictly two-dimensionally and the position of each instrument, on the grid, always affects its music in some way. For example, in the longest section of the piece, the position of each instrument determines both its relative occurrence with respect to the other instruments of its type and its dynamic, the predominant instruments spiralling slowly outwards from the centre of the group as the section progresses. In performance, therefore, the space analyses many aspects of the structure. Space is also used in its own right, as when, for example, the ’celli on the perimiter of the grid recall the smaller circle of clarinets.

The piece represents the first practical application of my theoretical deliberations of the previous years. This theory deals in essence with naturally occurring relations between hierarchies. In particular, it deals with those hierarchies which lie in fields whose structures give Vectors its name. It is possible to hear this music purely in terms of the proportions between elements, but it should be remembered that one of my chief concerns is an investigation of the characteristic ways in which various parameters can be meaningfully related. It is clear that I am much indebted to certain classic serial ideas, but there is at the roots of my work an emphasis upon the cardinal importance of the identity function which is leading me on a rather different path.2

Some General Ideas

One of the principal functions of Art, and in particular of composition is to explore the limits of our comprehension. I am convinced that invention is closely linked to the phenomenon of understanding. It confronts us with situations which lie a little outside the boundaries of our knowledge in order that we can extend those boundaries. Invention is the window in otherwise closed systems of ideas. The point of this exploration is not only that we thereby understand more (giving us more powerful tools for the control of our surroundings), but that we are occasionally allowed to feel the limits of our capacity for knowing.

I am deeply fascinated by the occurrence, in strict circumstances, of facts which defy explanation in terms of the strictness which gave rise to them. I believe that the correct approach to this rare but important situation is simply to accept that the frame of reference is not adequate to describe the reality. We must be very careful to avoid wilfull ignorance, but on the other hand we can no longer pretend to be omniscient.

It is for these reasons that I want to create a music in which pure chance plays no part. To include “free”, non-systematic elements is to ossify research by creating a blanket explanation for a multitude of problems. We should not allow the apparent freedom which we have in the definition of axioms to justify a failure to work out their consequences. All systems should be pursued to the point of absurdity, and the further that pursuit takes us, the better.

_____

1 Footnote 1978: “octave” in this context refers to the proportion 1:2.

2 Footnote 2025: This paragraph is referring to my project for developing a theory of “krystals”.

See A short introduction to krystals.

was conceived and executed.

was conceived and executed. was conceived and executed.

was conceived and executed. (page 1 of 37)

(page 1 of 37) ) omitting material at the end of a bar when the corresponding beat for the next bar is given by the conductor.

) omitting material at the end of a bar when the corresponding beat for the next bar is given by the conductor. at the end — having dropped three degrees from

at the end — having dropped three degrees from

. The length of the beam attached to each barline denotes the permissible area of uncertainty in the position of that barline.

. The length of the beam attached to each barline denotes the permissible area of uncertainty in the position of that barline.

ad lib. until

ad lib. until  .

.

and

and  (pages 2-3 and 3-13 of 37)

(pages 2-3 and 3-13 of 37)

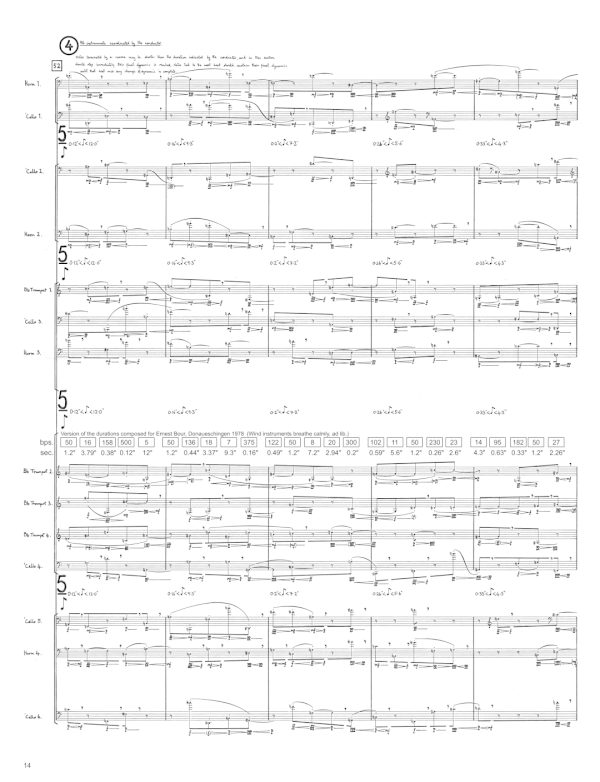

(Pages 14-15 of 37)

(Pages 14-15 of 37)

(page 16 of 37)

(page 16 of 37)

(pages 17-34 of 37)

(pages 17-34 of 37) (at the top and bottom of page 17) read as follows:

(at the top and bottom of page 17) read as follows: ) indicates that the notes within it succeed each other without a break, but that they each have a separate attack. The square slur is replaced by cross-beams for units of

) indicates that the notes within it succeed each other without a break, but that they each have a separate attack. The square slur is replaced by cross-beams for units of  and smaller in order to appear more orthodox and thus easier to read. When both square slurs/cross-beams and round slurs appear

(

and smaller in order to appear more orthodox and thus easier to read. When both square slurs/cross-beams and round slurs appear

(

,

,

) the notes are of course performed without re-attack (in the normal way).

) the notes are of course performed without re-attack (in the normal way). )

)

(at the top and bottom of page 32) read as follows:

(at the top and bottom of page 32) read as follows: s continuously until the last beat before

s continuously until the last beat before

(which must not be subdivided). However, these divisions will have no relation to particular notes in the music (there is of course a range of positions for each of these beats.) The notation means that the limits of the notes under the bracket are equal to 1/6 of the limits of a

(which must not be subdivided). However, these divisions will have no relation to particular notes in the music (there is of course a range of positions for each of these beats.) The notation means that the limits of the notes under the bracket are equal to 1/6 of the limits of a

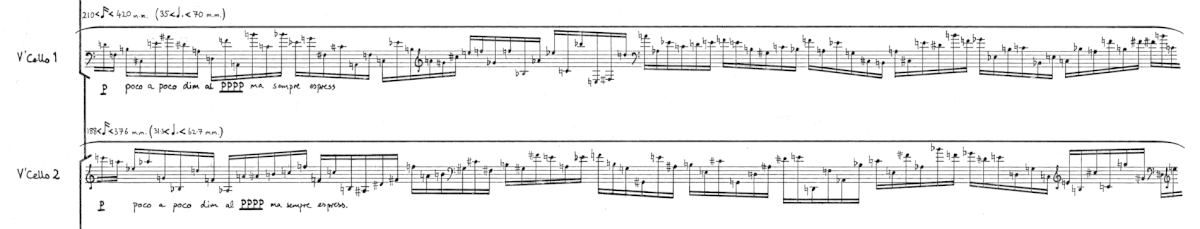

< 420 m.m. ( 35 <

< 420 m.m. ( 35 <

< 70 m.m.)

< 70 m.m.)

, none is comensurable. It follows from this that it is impossible to be sure of accuracy at the given limits of the durations. However, within each “tempo” field every player should ensure that

, none is comensurable. It follows from this that it is impossible to be sure of accuracy at the given limits of the durations. However, within each “tempo” field every player should ensure that

etc. This is exactly equivalent to the situation in metred music where it is impossible to guarantee the metronomic value of a beat, but it is possible to ensure that all beats are “equal”. Each duration in Vectors must be felt as a continuous phenomenon whose end-points are dictated by the phrasing alone, and not as the distance between two preconceivable points. For example, section

etc. This is exactly equivalent to the situation in metred music where it is impossible to guarantee the metronomic value of a beat, but it is possible to ensure that all beats are “equal”. Each duration in Vectors must be felt as a continuous phenomenon whose end-points are dictated by the phrasing alone, and not as the distance between two preconceivable points. For example, section  but the beats remain of the same form as those in the rest of the piece. This is not a bar in which the beats are equated with a regular pulse, it is rather the limit of an approximation.

but the beats remain of the same form as those in the rest of the piece. This is not a bar in which the beats are equated with a regular pulse, it is rather the limit of an approximation.

covers the available positions of that barline with respect to the music notated beneath it. Each player performs his or her music freely within the given limits of duration, jumping to the next bar when it is given by the conductor, omitting any material which lies between. This jump should always occur from a point under a horizontal beam. However, the notes which occur immediately after the barlines in these sections need not be completely simultaneous unless accompanied by a vertical arrow. They are nevertheless nearly so,

covers the available positions of that barline with respect to the music notated beneath it. Each player performs his or her music freely within the given limits of duration, jumping to the next bar when it is given by the conductor, omitting any material which lies between. This jump should always occur from a point under a horizontal beam. However, the notes which occur immediately after the barlines in these sections need not be completely simultaneous unless accompanied by a vertical arrow. They are nevertheless nearly so,

are a development towards an equivalent of the subdivisions in metred music (whereby a

are a development towards an equivalent of the subdivisions in metred music (whereby a

for example) by the controlled loosening of a homophony. The instruction at

for example) by the controlled loosening of a homophony. The instruction at

,

,  etc.). I have used them here to describe bands of possible durations, one octave1 each in width. It follows from this condition that exact performed durations are not predictable, and that they are not subdividable. Further results of this situation are that the ability to create multiple simultaneity of attack is concentrated in the hands of the conductor, and that there is a strong separation of the functional characteristics of attack, duration and release. It is perhaps interesting to remember that the traditional symbols for dynamic, the other dimension of size, also express bands of possible values.

etc.). I have used them here to describe bands of possible durations, one octave1 each in width. It follows from this condition that exact performed durations are not predictable, and that they are not subdividable. Further results of this situation are that the ability to create multiple simultaneity of attack is concentrated in the hands of the conductor, and that there is a strong separation of the functional characteristics of attack, duration and release. It is perhaps interesting to remember that the traditional symbols for dynamic, the other dimension of size, also express bands of possible values.